Chủ Nhật, 21 tháng 7, 2013

Celebrating the Mizo Paikawng: Reflections on The Three Orders of Design

Thứ Ba, 26 tháng 2, 2013

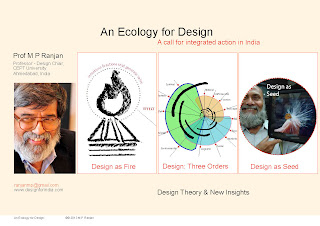

An Ecology for Design: A call for integrated action in India

An Ecology for Design: A call for integrated action in India

I was invited to a panel discussion at MICA, Ahmedabad (MUDRA Institute of Communication) as part of the National Seminar on Ecology, Communication and Youth: An ICZMP initiative at MICA campus, Shela, Ahmedabad from February 25 – 27, 2013 organised in partnership with, Gujarat Ecology Commission (GEC).

The participants were NGO's and Field workers who are all youth from across the country, ecology and communication scientists and researchers and I was asked to speak in Hindi, which I did. The speakers at my session were scientists from ISRO, SAC and International expert in disaster management and the title of the session was Science and Arts for Managing Coastal Resources and as usual design was missing from the session title. My paper that I presented at the seminar is quoted below and the visual presentation can be downloaded from this link here as a pdf file.

Download visual presentation here as a pdf file 3.8 mb

Text file of my lecture is here as a pdf file 65 kb size

I did not stick to the text submitted below but I did vent my thoughts on the disparity in funding and support from the Governemnt of India as well as the States for science and technology when compared to design although the premier Institute for design has now (finally) been accorded National recogntion by the Union Cabinet with the status of an Institute of National Importance. The scientists present at the seminar conferred with me and in response to my enquiery told me that the SAC gets about Rupees 600 crores a year and the parent organisation ISRO gets Rupees 6000 crores per year as their annual budget support for the year. Add to this the Rupees 5000 crores per year that is given to the CSIR and many hundreds of thousands more to defence and other sectors in the name of technology you will see that there is a complete absence of support for design in comparison. My stated position is that our country will not be able to solve its critical problems if this kind of disparity of funding continues in the future and I hope this message is heard and acted upon by the Finance Minister in his forthcoming budget or in a followup action when the matter of design as an activity of national importance is brought before the Indian Parliament, hopefully soon.

An Ecology for Design: A call for integrated action in India

M P Ranjan

Professor – Design Chair, CEPT University

Ahmedabad

Presentation at National Seminar on Ecology, Communication and Youth at MICA, Ahmedabad on 26 February 2013

Preamble

Quote from her “A Note from the Author”

“As corporations, which play such a powerful determining role in our species’ behavior as a whole, understand and abide by the sustainable survival principles of living systems, their goals will come into harmony with our personal and community goals. We can then mature like other species from competition to cooperation and build a human society in which the goals of individual and community, of local and global economy, of economy and ecology are met. This will shift us out of crises and into the happier, healthier world of which we all dream. Let it be so!”

Elisabet Sahtouris, September, 1999

as quoted in Elisabet Sahtouris and James E Lovelock, Earthdance: Living Systems in Evolution, iUniverse, 2000 (ISBN-13: 978-0595130672) This excellent book can be downloaded from her website here. or from a direct link as a pdf file here Earthdance.pdf 800kb

Ecology and Design

For me the seminar at MICA that will focus on the ecology of coastal Gujarat is an occasion to reflect on the terms – “Ecology” as well as “Design” – since both of these for me are central for understanding the world as a system and not as a collection of parts that we most times tend to do in order to achieve administrative convenience.

The word Ecology is perhaps well understood by this gathering as the overarching processes of nature that includes the scientific study of the relationships that living organisms have with each other and with their natural environment. It alludes to the manner in which the various parts of the natural environment relate with each other and contributes to the sustainable survival or demise of the whole system.

My definition of the word Design, however, may not be generally known nor accepted easily since we all carry so many versions for this particular word. So let me state it here in brief to explain my arguments further.

Design is a cultural system just like literature, music, art and philosophy. Design is driven by human intentions and actions that shape our environment and over time it shapes us and the culture and values that we hold dear. It is not only informed by culture, but also helps create it and is one of the central contributors of both the tangible and intangible resources of any cultural entity through a constant process of evolution and assimilation that these living cultures tend to do. Design at a deep level deals with all aspects of human evolution and in the production of culture through the human use of local resources as well as the unfolding of human imagination and political action that brings change. Therefore this search is not just for truth that exists (which is what science does) but a search for what could be the imagined possibilities and options and these are preferably aligned with an existing trajectory of culture so that it is more acceptable to local inhabitants and the holders of that particular culture. Therefore, design imaginations offerings cannot be tested in a laboratory but can only be manifested in the world through its acceptance by the people who wish to own it and put it to use. They need to be prototyped and visualized at an early stage and then taken through many stages of refinement and testing before a wholesale adoption of the se offerings can be made practical and desirable. Design is also a profession and here our understanding of its knowledge, skills, sensibilities and its scope are all changing as we continue to gather insights from our practice and research here in India and today it is substantially different form when it was introduced as a modern discipline in India some fifty years ago

Design is a discipline that uses all the disciplines known to humanity in order to build a synthesis of new offerings –settlements, products, spaces, services, activities as well as organizations – for the betterment of our society and to meet their aspirations, needs and desires with the natural and cultural resources that are available and accessible at any given time and place. Over time, what we build tends to shape us and all that we think and do.

Design as a System

I have used the metaphor of fire to define design using a model that was developed with my students. When we look at fire we see that it has various components — Fire (Agni) is a process of transformation — a material is transformed by organic exchanges with the environment and an effect is the product of this exchange. The process is always situated in a particular context and this context is represented by the ground on which stands the fire, both time and place taken together form the context. The process of burning and the products of light, heat and smoke are all in close interplay with the environment and design too is an activity that can happen only with reference to its own context. This fire therefore represents the kind of complex transaction that I consider an adequate expression for the systems metaphor for design.

This means that we see design as a complex activity. There is not a single product that we can call a simple product. Take for example the simplest of products that you can think of and explore its possible effects. If you look at it only as a product of technology, that is, as some material transformed into a functional shape, then it would seem to be simple. However if you consider its entire life-cycle and its impact on society, it is quite another matter altogether. So it is becoming increasingly evident that design has to look beyond the object itself as a mere artifact, as produced by technology, to the effects that these objects have on a complex set of user-related parameters and finally the effects of these objects on the environment and culture at various stages of their life cycle need to be taken into consideration while we design them.

This leads us to re-evaluate the role of design and to anticipate the shape of the design activity in the years to come. We are beginning to understand the complex nature of design, which means that you also need a fairly complex method of dealing with it. Design methodologies need to be reevaluated and innovated to cope with this complexity. A lot of technological development in recent years has created negative results, some with catastrophic consequences. We are certain that the exploitation of technology without the use of design processes that take cognizance of the long term needs of users and environments will lead to disaster.

We can call this an ecological view of design when we are attempting to deal with the complexity of both natural systems as well as how they connect and are influenced by human interventions and activities.

Three Orders of Design

In a paper that I had presented in Istanbul in 2009 titled:” Hand-Head-Heart: Ethics in Design” I had proposed a new organization of our understanding of the design activity as the three orders of design.

The “Ethical Design Vortex” that moves through these three orders in sweeping and overlapping stages includes various manifestations of design thoughts and actions along a growing spiral of influences and categories listed below:

• The First Order of Ethics in Design

Material – Craftsmanship – Function – Technique – Structure

This level of design is recognized by most people and is the commonly discussed attribute. Here material, structure and technology are the key drivers of the design offerings as these help shape the form that we eventually see and appreciate in the artifact. We can appreciate the offering as an honest expression of structure and material used and transformed to realize a particular form that is both unique as well as functional. It is here that skill and understanding of the craftsmen are both used to shape the artifact through an appropriate transformation with a deep understanding of its properties and an appreciation of its limitations.

• The Second Order of Ethics in Design

Economy – Society – Communication – Environment

This level is influenced by utility and feeling of a society and is largely determined by the marketplace as well as by the culture in which it is located. Here aesthetics and utility are informed by the culture and the economics of the land. We can sense and feel the need for the artifact and the trends are determined by the largely intangible attributes through which we assess the utility and price value that we are willing to accord to this particular offering, which is quite independent of its cost.

• The Third Order of Ethics in Design

Politics & Law – Culture – Systems – Spiritual

This level is shaped by the higher values in our society and by the philosophy, ethics and spirit that we bring to our products, events, systems and services. At this level value unfolds through the production of meaning in our lives and in providing us with our identities and these offerings become a medium of communication in themselves, all about ourselves. It is held in the politics and ethics of the society and is at the heart of the spirit in which the artifacts are produced and used in that society. There are deeply held meanings that are integral to the form, structure as well as some of the essential features which may in some cases be the defining aspects of the offering, making it recognizable as being from a particular tribe or community. These features define the ownership of the form, motif or character of the artifact and these are usually supported by the stories and legends about their origin and give meaning to the lives of the initiated.

Conclusion

I do not have much time to elaborate these positions and provide all the case studies that we have gathered over the years. These are described in my previous papers as well as on my blog – “Design for India” – and can be accessed from there. However this presentation will not be complete without stressing that we need to build a suitable ecology for design itself to flourish here in India since we seem to have adopted specialization as our preferred approach to dealing with problems as and when they crop up while relegating the organized integration of these special knowledge and tools to chance encounters of committees that we put together to manage these events as they come to our attention. On the other hand we speak of public private partnerships where we place these actions in the hands of some entrepreneur who is supposed to first create these new offerings by inventions and also “jugaad” without the benefit of a nurturing environment on which these activities can take place in a sustained and effective manner. India needs to reconsider its approach to design and to recognise design as an ecological offering that has many layers and relationships and also to set up processes and organisation that can use that language and tools of design to transform our society and the environment on which they live, work and play. We will also need to look at the manner in which design can be integrated into all our activities and not leave them as domains of specialist activity as they have been in the past. For this to happen we will need to look at how design is being taught in our schools and institutes and how these will change to accommodate the new understanding of design that we now have arrived at through our various journeys and from the crisis that some of our past actions have created at the level of the ecology, while looking at the health of the whole and not just the parts.

References

1. Elisabet Sahtouris and James E Lovelock, Earthdance: Living Systems in Evolution, iUniverse, 2000 (ISBN-13: 978-0595130672)

2. Harold Nelson and Eric Stolterman, The Design Way, (Second Edition)

Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World, MIT Press, 2012 (ISBN: 9780262018173)

3. M P Ranjan, blog “Design for India” www.designforindia.com

About the Author

M P Ranjan

Professor – Design Chair, CEPT University

Design Thinker & Author of blog www.designforindia.com,

Ahmedabad

Prof M P Ranjan is a design thinker with 40 years of experience in design education and practice in association with the National Institute of Design. He helped visualize and set up two new design schools in India, one for the crafts sector, the IICD Jaipur and the other for the bamboo sector, the BCDI Agartala. His book Handmade in India is a comprehensive resource on the hand crafts sector of India and was created as a platform for the building of a vibrant creative economy based on the crafts skills and resources identified therein.

His book on bamboo opened up new frontiers for design exploration in India. He has explored bamboo as a designer material for social transformation. Bamboo has been positioned as a sustainable material of the future through his work spread over three decades. His work in design education covered many subjects including Design Thinking, Data Visualisation, Interaction Design and Systems Design

His blog “Design for India” has become a major platform for Indian design discourse.

He is on the Governing Council of the IICD, Jaipur and advises other design schools in India and abroad. He lives and works from Ahmedabad in India. He has been acknowledged by peers as one of the international thought leaders in Design Thinking today

~

Thứ Hai, 27 tháng 4, 2009

What is Design? : A lecture for school teachers

What is Design? : A lecture for school teachers

Design for India: Prof M P Ranjan

Image 01: Thumbnails of slides used for the “What is Design?” lecture dealing with Dimensions, Processes and Applications.

“What is Design?”, will be a perennial topic since design is and will always be a moving target whenever we attempt a definition since it is always rooted in the present time and can only be understood and appreciated in the context of the “particular” place or location and a “general” description will need to take that into account as well. Each age will need to take stock of the definition and as we evolve so will design and hopefully our design ability. Design is one of our basic abilities, which we have used in more and more sophisticated ways as we evolved and enhanced our human sensibilities and capabilities. In the period of slow transformation through craft based processes of trial and error many of these sensibilities were refined and we could fall back on traditions to find our way forward.

Image 02: Thumbnails of the second part of the lecture dealing with design concepts and models that lead to our current definition of design as a basic human activity and this calls for a greater focus for the subject in our school education in the days ahead.

However in the post-industrial era reach and impact of our senses and abilities have been considerably enhanced by our multitude of tools and our externalized knowledge processes that we now have the capability of changing and impacting nature in dramatic ways, many of them undesirable, and our economic and social frameworks lag behind by a huge magnitude, that we are on the brink of failure as a species. Design becomes all the more important in this scenario and we will need to temper our dependence on science and art which has helped us evolve very rapidly over the past 600 years since the Renaissance if we are to face the crisis that this dependence is to be addressed.

===============

===============

Code to embed podcast of lecture sent by Satya Murthy using MP3 file provided by me.

I had the occasion to speak to a group of school teachers as part of our programmes at NID and I prepared a lecture that was delivered to this group at NID the other day. The recording of the lecture is available here as a podcast at the link above which is of one and a half hour duration and the 2.5 MB pdf file of the slides used lecture can be downloaded from here at the links below along with an MP3 file of the lecture which too is available for download as a 45 MB file

Link to download the Podcast with images

What is Design? : Dimensions, Processes and Applications (pdf file 2.3 mb download)

What is Design? : Dimensions, Processes and Applications (MP3 voice file 43.8 mb download)

Design for India: Prof M P Ranjan

Thứ Ba, 17 tháng 2, 2009

The Three Orders of Design: Lessons from Northeast India

The Three Orders of Design: Lessons from our study of the baskets from Northeast India

Prof M P Ranjan

Design overview lecture delivered at the “Uttar Purva Utsav” organized by the Crafts Council of India at the “Dilli Haat” on 2nd February 2009 to celebrate and promote the crafts of Northeast India in association with the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, Government of India.

The lecture was simultaneously translated into Hindi by Ms Asha Bakshi, Dean Fashion Design, National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), New Delhi.

Image01: Speakers at the “Uttar Purva Utsav” organized by the Crafts Council of India at Dilli Haat in early February 2009.

This invitation to speak at the “Uttar Purva Utsav” organized by the Crafts Council of India at the “Dilli Haat” gives me the opportunity to reflect on my three decade old association with the crafts of the Northeastern Region of India and to ponder on the lessons that we have learned about design and bamboo from the craftsmen of the Northeast over the years since our first contact with their work in the field in late 1979. We began our year long fieldwork November 1979 in the Northeast as part of the project sponsored by the All India Handicrafts Board in those days, now the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts [DC (H)], to study the bamboo and cane crafts of the region which resulted in a book which was eventually published in 1986 by the DC (H) and the National Institute of Design (NID), titled “Bamboo & Cane Crafts of Northeast India” by M P Ranjan, Nilam Iyer and Ghanshyam Pandya. (download book here as PDF file 35 mb size) It is also an opportune occasion to connect once again with the resources that were generated by that project particularly in the form of the very large collection of baskets that were collected in the field as part of our study and these are today available at the National Crafts Museum and I am told that these are on special display to celebrate the crafts of Northeast and in conjunction with this particular event at the Dilli Haat. The craftsmen and the crafts promoters are invited to visit the National Crafts Museum at Pragati Maidan and see for themselves the quality of crafts that is still a living tradition of the region as these products are still in active use across the region but times are changing fast and these may not remain that way for very long. Digital pdf copies of my book can be downloaded from my website and in-print copies of the paperback edition (2004) are available from both NID and the DC (H) and the original hard-bound edition (1986) is now out of print.

Image02: The Paikawng from Mizoram, side and top view seen with drawings of the base, sides and rim construction and the detail of the base strengthening detail using cane binding over a bamboo base.

I must share the learning that we were able to glean from our journeys into the Northeast as well as from our interactions with the local craftsmen which was followed by a period of deep study that we could invest into the collection of 400 baskets that we had gathered during our field work in the Northeastern region. Besides giving us numerous insights about bamboo that were invaluable we were also quite surprised to see the deep appreciation of design principles that were both applied by the craftsmen as well as something that we found embedded in the range of products that we had collected in an extremely selective manner during our year long field work in the seven states of the Northeastern region. Now Sikkim has been included in the definition of the Northeastern Region and rightly so, since these states share so many common characteristics with each other while keeping their individual identities intact. Learning from the Northeast’s craftmen was an exhilarating experience and in all very enriching experience. As a designer and a design teacher traveling with two colleagues through a culture that was rich with knowledge about bamboo and design it was a stimulating experience for us and a huge source of new learning from the field. This learning we tried to capture in our book about the Bamboo and Cane Crafts of the Northeastern Region and while the content may look like a normal documentation a look at the back of the book will reveal a meta-structure of information and local knowledge contained in two indexes, one a “Technical index” that captures all the nuances of the local wisdom across many fields and the other a “Subject index” which links and makes accessible word concepts as they appear across the book. Our sense of amazement at each product that we saw and the level of detail to which the thought process had helped evolve that product was always a source of great pleasure, amazement and admiration. From all these products I would like to draw out one specific example, The Paikawng, a Mizo basket used for carrying firewood, not because it stands above the rest but simply because it is one of many products that come to my mind as I stand here and reflect on our deep learning from the field about design itself. I will therefore use the example of the Paikawng to set out the boundaries and contours of the three orders of design as they appear in the fine hand crafted baskets of Northeast India.

Inage03: A general understanding of structure of baskets from Northeast India from our book along with two particular baskets from the Tengnoupal hill district of Manipur State, one closed-weave for grain and the other open-weave for grass and fire-wood.

Let me first give you an overview of the three orders of design that I shall be dwelling on over the next few minutes. What are these and how do they relate to our understanding of design and in particular how these can help us use design to further our objective of building better products and systems for the people of the Northeastern region? The fine detailing in the baskets from the Northeast represent the climax of a bamboo culture and the field study and our book tries to pay homage to that spirit. The three orders of design are listed here and I shall proceed to explain how these were appreciated in the Paikawng and in all the other products that were equally rich and deserving of our attention.

The First Order of Design:

The Order of Design of Material, Form & Structure

This level of design is recognised by all people and is the most commonly discussed attribute. Here material, structure and technology are the key drivers of the design and these help shape the form that we eventually see and appreciate in the product. We can appreciate the product as an honest expression of structure and material used and transformed to realize a particular form that is both unique as well as functional. It is here that skill and understanding of the craftsmen are both used to shape the product through an appropriate transformation of the material with an understanding of its properties and with an appreciation of its limitations and possibilities.

Image04: Description of the open-weave structure and its varients from the Northeast and the Paikawng shown in use for fire-wood carrying from the pages of our book.

Let us take the Paikawng and examine it at the level of material and form – this basket is made of long strands of stout bamboo splits that are first interlaced to form a square base before these are bent up to form the sides of the basket. In forming the sides these very same splits form elongated hexagons that are a result of the three horizontal bands that anchor the inclined verticals between the base and the rim structure. At the rim these splits are each divided laterally into a number of sub-splits which lend themselves to a form of braiding so as to create a wide braided band that is both soft as well as very strong but being flexible. The material of the split is thus transformed at each stage, the base as flat and wide, the sides as thick and stiff and the rim as soft and flexible, while still remaining one single piece of bamboo that is responding to a particular structural need at the point where it is needed. The four corners of the square base are covered by a interlacing knot, each made of a length of cane splits which does not unravel easily if some of the overlapping strands are cut while the basket is in use. Cane, here is used sparingly to conserve costs and to save the critical part of the bamboo basket from friction and were and tear at the corners which are the most vulnerable parts of this basket when in contact with the ground. Further, this additional feature can be renewed or replaced in case of damage in use and the whole basket would therefore have an extended life. This lends the basket a degree of toughness that is essential for the intended function, which is to carry rough cut fire-wood from the field to the home and this brings us to the second order of design.

The Second Order of Design:

The Order of Design for Function & Feeling – Impact & Effect

This level is influenced by utility and feeling and is largely determined by the marketplace as well as by the culture in which it is located. Here aesthetics and utility are informed by the culture and the economics of the land. We can sense and feel the need for the product and the trends are determined by the largely intangible attributes through which we assess the utility and price that we are willing to pay for this particular offering and this is quite independent of its cost.

Image05: Pages from the book “Bamboo & Cane Crafts of Northeast India” showing the construction of the Paikawng in line drawings of base, sides and rim structure with description of its uses at home and at work.

In order to examine this level of design we will need to compare similar products across a number of different social and cultural situations. Firewood baskets are made by many communities of the Northeast and each of these have a distinctive form that is informed by the asthetic preferences of that community. The Paikawng offers the Mizo a particular form and structure and for lighter applications they have a sister product called the Emsin which is lighter and smaller than the Paikawng but with very similar structural and formal characteristics of the latter. The other tribes have distinctly different forms that are arrived at by differences in the size, shape, contours as well as the shape of the hexagon used to form the sides of the baskets in question while addressing the same set of functions that the Paikawng addresses for the Mizos.

The Third Order of Design:

The Order of Design for Value – Meaning and Purpose

This level is shaped by the higher values in our society and by the philosophy, ethics and spirit that we bring to our products and events as well as all the associated services and the stories that we can tell about the relationships between these entities and our lives. At this level value unfolds through the production of meaning in our lives and in providing us with our identities and these products becomes a medium of communication itself, all about ourselves. It is held in the politics and ethics of the society and is at the heart of the spirit in which the products are produced and used in that society. There are deeply held meanings that are integral to the form, structure as well as some of the essential features which may in some cases be the defining aspects of that product, making it recognizable as being from a particular tribe or community. These features define the ownership of the form, motif or character of the product and these are usually supported by the stories and legends about their origin and these give meaning to the lives of the people for whom they are made.

Image06: Views and description of the Emsin, a sister product of the Paikawng which is used for lighter tasks and as a ‘fashion’ product by the Mizo youth for visits to the bazaar and other light chores.

The Paikawng has this distinctive character and can be recognized as a typical Mizo product both by the Mizos themselves as well as by those around them. The braided band at the rim has a unique name in the Mizo language – it is called “vawkpuidang phiar”, meaning “the braided pattern or palete of the pig or sow” which has a similar knitted pattern. These stories bring value to the product that goes far beyond its material and utility value that is usually embedded in such functional products. We need to recognize the characteristics that these three orders of design bring to the contemporary products of our own society and in doing so we can learn to enhance the value that it brings to the market as well as tone the quality standards that are applied to each instance of these products at the various stages of production, marketing and utilization in the society.

All three layers are important and we need to learn to appreciate our creations along all three axis if we are to reach a sustainable offering in the handicrafts sector in the days ahead. Design therefore has a number of layers that are addressed in our traditional artifacts and when we embark on the making of our new and innovative products for new markets we will need to pay a great deal of attention to all three orders of the design spectrum if we are to reach a semblence of sustainability and order in our creative offerings for the future.

Download the book here: 35 MB PDF

M P Ranjan, Nilam Iyer and Ghanshyam Pandya, "Traditional Wisdom: Bamboo and Cane Crafts of Northeast India", Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, Government of India, New Delhi, 1986 (HB) & 2004 (PB)

Prof M P Ranjan